The Urban Heat Island Effect: A Growing Threat to Human Health in Tacoma.

Do you remember where you were on June 28, 2021?

That was the hottest day ever recorded in many Pacific Northwest places thanks to a freak "heat dome" sitting over the region. That weather event shattered heat records and would not have been possible without climate change. Like firenado, derecho, and polar vortex, heat dome quickly became part of our climate change lexicon.

It was 108 degrees at SeaTac Airport; counties south and west of Tacoma even tied the state heat record with measurements of 118.

Sunset behind St. Joseph Medical Center, Tacoma, June 27, 2021.

Photo Credit: Bonney Elizabeth.Over the course of that three-day heat event, many of us who were able sought refuge among the trees and along the coastlines of Tacoma. Chambers Creek in Steilacoom was full of people wading in the stream. Owen Beach at Point Defiance was covered with folks cooling down in the water. In times like that, it seems so obvious that parks, forests, and shorelines are part of the critical infrastructure of our city: The trees and waters literally cool the air, sometimes by as much as 10 or 15 degrees compared to other areas.

Now imagine stepping back out of the trees and into a treeless parking lot. Heat radiates all around you—from above and below. Sweat breaks out across your forehead. Your skin begins to bake. You need to find protection. If you can't, your health—and even your life—may be at risk.

While the forest and the parking lot represent the temperature extremes within a city landscape, this phenomenon of temperature disparities plays out on a larger scale across urban areas every day. Some neighborhoods are consistently hotter than others due to historical racism and unequal levels of infrastructure investment, impermeable surfaces (like pavement and roofs), and, of course, tree canopy coverage. The hottest neighborhoods in a city are known, simply, as urban heat islands. They can be as much as 20 degrees hotter than surrounding areas and are generally found in neighborhoods with more poverty, more racial-ethnic diversity, and less tree canopy coverage. Urban heat islands are a serious environmental justice issue that we are only beginning to understand.

They exist because of the broad range of public policies—from redlining to landscaping codes—that dictate how a city physically develops. How much pavement should it have? How many trees should there be? Should there be parks in all neighborhoods, or only some? How much is the government responsible for public health and safety? How much oversight should there be when it comes to how the landscape is managed? With climate change shattering global temperature records and making heat domes possible in the usually temperate PNW summer, these questions are becoming more urgent all the time.

In Tacoma, where most people do not have air conditioners, the 2021 heat dome was a public health disaster and a wake-up call. The National Weather Service warned that Western Washington pavement could reach 170 degrees. 138 people died across the state, including eight Tacomans. Most of them lived in neighborhoods that were redlined in the 20th century and lack tree canopy coverage today. Those neighborhoods also have more pavement, which traps heat and prevents cooling overnight. One person died of heat exhaustion while sitting in his home with the fan on. The neighborhood was simply too hot.

We know where these urban heat islands are thanks to a 2018 analysis led by Dr. Vivek Shandas of Portland State University, who has presented for us about this issue in the past. Dr. Shandas, the foremost national expert on the urban heat island effect, worked with his students and the City of Tacoma's Environmental Services department to measure heat across Tacoma neighborhoods at different times of day. (They basically drove around town with heat sensors attached to cars—science is awesome!)

So we already know where Tacoma's heat islands are. What now?

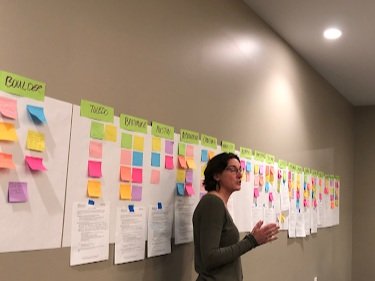

Recently, a Tacoma-based group of public and private partners* that includes Tacoma Tree Foundation, applied for and was accepted into an "accelerator" program from the Boulder, Colorado-based Center for Regenerative Solutions (CRS). We became one of 16 groups from U.S. urban areas, including our neighbors in Portland and Seattle, to participate in the inaugural program. The broad goals were to bring government and community-based organizations together to learn about the topics of urban heat, urban forestry as a nature-based solution, equitable community engagement, career pathways, and public policy. CRS convened a series of informative and collaborative webinars on all these topics, supplemented by resources for further reading (all available here!).

Another goal was to encourage planning and knowledge sharing related to the historic levels of funding for urban forestry programs. Over the course of the summer, many of us applied for federal funding to conduct urban forest programs in diverse and underserved communities. (Unfortunately, Tacoma Tree Foundation and Pierce County's proposal to extend our Green Blocks program across the whole Tacoma urban area was not funded in the first round, but we will have other opportunities to apply for some of the same funding in the coming months!)

The program culminated with an in-person conference in Cleveland, Ohio, on October 11–13, 2023. I was able to attend and was joined by Jess Stone, the Natural Lands Steward for Pierce County (and former TTF Board President).

Jess Stone presents an urban forestry pitch for Tacoma-Pierce County at the Urban Nature-based Climate Solutions Accelerator. October 2023.

Photo Credit: Lowell Wyse. We were joined by roughly 50 other people from those 15 cities (including Dr. Shandas), and the relatively small group size contributed to many excellent conversations over meals and during workshops. We also worked in groups to refine our grant funding pitches. Jess's energetic presentation was a crowd-pleaser!

Participants gather in a greenhouse at Rid-All farms in Cleveland, Ohio. October 2023.

Photo Credit: Lowell Wyse. One of the highlights of the conference was a trip we took to Rid-All farm, a 17-acre Black-owned urban farm in the heart of Cleveland. Our hosts there shared a message of hope and a vision of community-driven land stewardship in underserved urban areas. The partners at Rid-All have turned a neighborhood of burned-out houses known as "The Forgotten Triangle" into a vibrant green space and a center of Black environmental care and teaching. They are doing cutting-edge projects related to soil nutrition and hydroponic farming, as well as pioneering the use of biochar to amend contaminated soil and stash carbon underground, all while heating their greenhouses with the wood gas that is burned off in the biochar process. These kinds of community-driven, nature-based solutions in environmental justice communities are a critical piece of the puzzle for creating more resilient cities in the 21st century. Above all, they give us hope in a time of climate uncertainty.

Can Tacoma become a Vanguard City?

At the end of our time in Cleveland, Jess and I were presented with a beautiful, one-of-a-kind cutting board created from salvaged urban wood by Cambium Carbon. It declares Tacoma a "Vanguard City" for urban forestry and countering the urban heat island effect. I received it with mixed emotions. Yes, we have learned in so much detail about the many problems that Tacoma's unfair forest poses for livability in a changing climate. And I am proud of how we at TTF are building neighborhood-based programs that allow the community to take action to plant trees and cool our unshaded neighborhoods.

Pictured, left to right: Jess Stone, Lowell Wyse.

Photo Credit: Lowell Wyse. But the very existence of urban heat islands—some of which encompass whole neighborhoods—represents an utter failure of leadership and vision over generations. And policy change is not coming fast enough (a topic we will explore more fully in a future post this fall). Tacoma is no closer to its goal of 30% tree canopy coverage by 2030, which would require planting 1 million large trees while also replacing every tree that is cut down. Our leaders need to recognize that urban trees are critical environmental and public health infrastructure that require protection and investment. Only then will we be on the path to becoming a resilient, vanguard city.

Accelerator program partners include Pierce County, Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department, City of Tacoma, Pierce Conservation District, and The Nature Conservancy in Washington. Special thanks to Marco Pinchot from Pierce County for completing the Accelerator application and keeping us all on track!

Right: Wooden plaque, created by Cambium Carbon.

Photo Credit: Lowell Wyse.